These past few weeks I spent some time playing This War of Mine: The Little Ones (TWoM). While TWoM is a game I will certainly return to over time, I have experienced enough of the hardships of war in my 7+ hour playthrough for the time being. The game is beautiful in that it is profound, but this is coupled with the weight of war and its consequences on civilians.

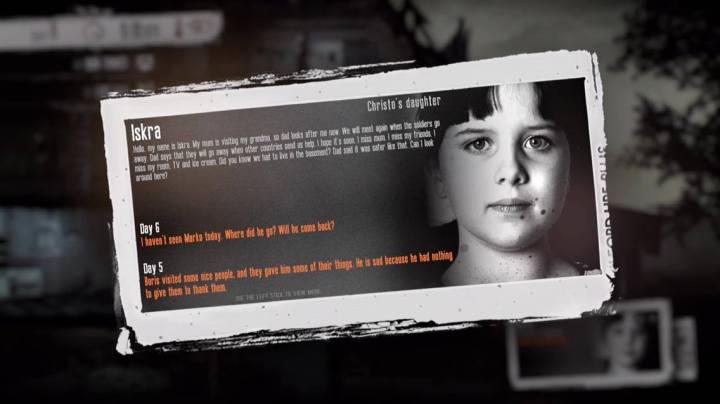

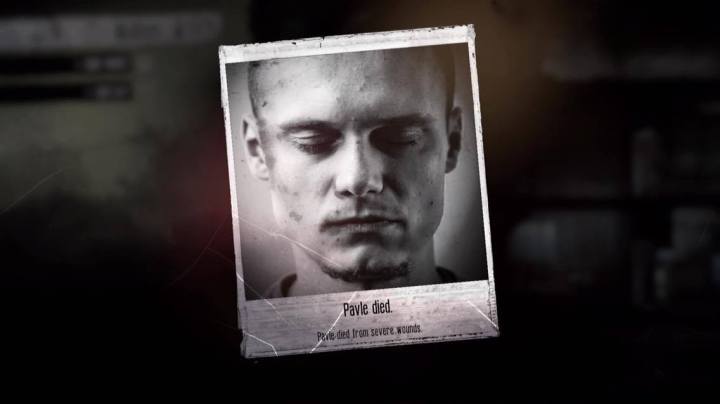

TWoM is a game where players take control of a number of civilians struggling to survive amidst a war-torn city. Players must manage each character’s level of hunger, health, comfort, and sense of safety while constantly sending characters out into the dangers of the city at night to scavenge for everything from precious food to crafting materials. Characters can be injured in skirmishes, bleed out and die, and become so catatonic they refuse to move or be consoled. I haven’t experience this yet, but I have also heard that characters can become so depressed as to commit suicide. The reality of war and its impact on civilians is inescapable in TWoM. And that’s the point. Adding to this somber experience is the major difference between this game and the previous releases on PC and mobile–children are now thrown into the mix.

Almost immediately into my first playthrough, I lost the child staying with me. He was a neighborhood kid I had taken into my small group in this custom playthrough. The child quickly became distraught over the near nightly raids that took place and even became injured during one of them. His mental well-being spiraled out of control, and I could not control his emotions or wailing. One evening the character I had sent out to scavenge for supplies returned to find an empty shelter. Marin, a man who recently joined my small group, had left with the child in hopes of finding a safer place to live and survive until the warfare ended. I never saw them again.

I was left staring at my TV screen for a few seconds. Two of my survivors left because I failed to create a safe and emotionally healthy environment for them to live. They were gone, and I could not get them back. Soon after my remaining survivor died.

As depressing as all this sounds, I appreciate the sense of uncertainty and anxiety the game creates. TWoM gives players options and leaves it up to players to decide when to venture out for supplies or how much medicine to give to someone, but the resulting consequences of those decisions can result in a loss of agency or, at least, a feeling of helplessness in the player. This is realistic on many levels and serves to make the game’s theme of war constant and inescapable.

Moral decisions abound in TWoM as well. Will you take advantage of the elderly couple in the quiet cottage and steal from them? Would you consider murdering them to save your own family? To be clear, murder is not necessary in the game, but certain situations might lead players to consider that option. Starvation is a huge source of motivation. At one point, I ran into a hostile character in an old church and killed him. My action was in self-defense, but the character I was controlling at the time was not consoled by this fact.