As a franchise, Far Cry has players take on the roles of protagonists who become heroes to specific communities–typically people who are presented as “primitive” in a variety of ways. The hero is capable of exceptional ideas and actions which in turn aid and lift local communities out from under oppressive forces. This is a common theme in video games. However, these relationships between “saviors” and “victims” can be problematic in Far Cry even if the last two games in the franchise make attempts to rectify or adjust such representations.

As a franchise, Far Cry has players take on the roles of protagonists who become heroes to specific communities–typically people who are presented as “primitive” in a variety of ways. The hero is capable of exceptional ideas and actions which in turn aid and lift local communities out from under oppressive forces. This is a common theme in video games. However, these relationships between “saviors” and “victims” can be problematic in Far Cry even if the last two games in the franchise make attempts to rectify or adjust such representations.

I’m going to look at the shift the developers have taken in depicting local populations and their respective heroes in the Far Cry franchise. I have decided to focus on the three latest standalone Far Cry games and not every entry in the franchise (only because it has been some time since I’ve played certain titles). Please note that I have played Far Cry 2, Far Cry 3, Far Cry 3: Blood Dragon, Far Cry 4, and Far Cry Primal (and I will play Far Cry 5).

Some definitions may help as a refresher of terms and how they are commonly used. A simple Google search of terms defines the following:

“Primitive”

[noun] “a person belonging to a preliterate, nonindustrial society or culture”;

[adjective] “relating to, denoting, or preserving the character of an early stage in the evolutionary or historical development of something.”

“Native”

[noun] “a person born in a specified place or associated with a place by birth, whether subsequently resident there or not”;

[adjective]: “associated with the country, region, or circumstances of a person’s birth.”

“Hero”

[noun] “a person, typically a man, who is admired or idealized for courage, outstanding achievements, or noble qualities.”

“Savior”

[noun] “a person who saves someone or something (especially a country or cause) from danger, and who is regarded with the veneration of a religious figure.”

Starting with the above definitions, I would like to create a kind of picture or profile that might help with analyzing the characters and motives in the Far Cry games. The lists below are based off of the previous definitions and my experiences with video games.

Quite often the heroes of video games are:

● male

● white

● 18-30 years old

● representative of Western culture

● “superior” to the population in need

○ not of the local population

○ physically and/or intellectually advanced/skilled

In turn, the native or local population is often characterized as being:

● sexual (especially in their manner or dress and behavior)

● intellectually simplistic or limited

● victimized

● religious

● superstitious

Note that all the items in these lists are not necessarily “bad” or demeaning as separate elements. More often than not, it is when these pieces come together to form a cohesive whole of respective local populations and hero figures that worrying narratives are shaped in video games. Much of what I am discussing depends on context.

As an educator’s aside, while hero or savior figures are nothing new in video games, their presentation in alignment with “primitive” or “less-advanced” populations merits some critical discussion if we recognize games as rhetorical objects. Games make meaning, influence player perspectives and expectations, and set precedents. In terms of education, games should not be underestimated as markers of culture and literacy.

I hope the following analysis will show how the above elements are reinforced and challenged in Far Cry 3 (FC3), Far Cry 4 (FC4), and Far Cry Primal (Primal) to form narratives where hero figures intersect specifically with native populations.

Far Cry 3

Jason Brody is the protagonist of FC3. He is a young, average college student on vacation when he and his friends are kidnapped by psychopathic pirates on the Rook Islands. Through the help of the island’s inhabitants, both natives (the Rakyat) and various other characters who have come to the island, Jason rescues his friends and “frees” the Rakyat from the drug smugglers/pirates (led by a wicked man called Vaas). Loss, adventure, and explosions ensue.

FC3‘s narrative quickly and absurdly stretches past the bounds of realism in typical AAA fashion. Players are expected to believe that Jason, shown previously having a good old time partying in a club with friends and traversing the island like a typical tourist, is aware and skilled enough to pick up guns and take on a group of pirates practically by himself. Sure, he witnessed his brother’s death, but let’s think about this. An organized group of pirates. He’s using guns with mastery (depending on the player’s skill level of course). Zero training. Gotcha.

Jason, as the white, male protagonist, is capable and believable because we, the players, have come to expect that any white, male protagonist is capable in video games. It is an established, albeit questionable, aspect of many video games, especially the action-packed, first-person shooter kinds. His youth and rage become the driving forces that lead to his acts of revenge and eventual liberation of the Rakyat. His capabilities are rarely questioned because players don’t question their perception of him. Players are not prodded to question Jason and his journey.

While Jason, an outsider, is presented as the hero the Rakyat need, it is also true that the island’s troubles were brought about by outsiders to begin with. As typically happens, the exposure to outside forces rarely brings anything other than conflict and bloodshed to the local population. It is then almost ironic that, as an outsider, Jason is the solution to the Rakyat’s woes.

Now, it could be argued that Jason had to become like the Rakyat and receive the tatau (tattoos of a warrior), but the key word here is “like.” Jason became like the Rakyat in some ways: he is allowed into their sacred temple and he is initiated into the tribe, but he can never truly be Rakyat. He quickly becomes obsessed with killing and even starts to forget about escaping and rescuing his friends. Jason’s progression through FC3 is a predictable story of journey and development.

However, one of the issues in this presentation is that the locals are unable to adapt and deal with the changes caused by foreign influences. Outsiders caused some major problems and only outsiders can solve them. Additionally, the only hero that can save them is white. The narrative smells of colonialism. And really, if FC3 were aware of its own colonial undertones and caused players to actively reflect and consider it, this might result in an okay story. The game fails to take this opportunity though. Instead, while many of the Rakyat villages are colorful representations of island life, they also demonstrate the squalor that the Rakyat live in. NPCs cough with illness, their living conditions are simple, and they fear for their lives on a daily basis. Without Jason, the Rakyat seem helpless.

They are a people torn between the “old ways” and the modern circumstances brought about by their interactions with outsiders. Even the pirates, many being from the islands, demonstrate the extent to which these interactions have affected the Rakyat. They have turned to exploiting their own brothers and sisters to engage and compete with outside sources. With the arrival of outsiders came turmoil as a result of greed and power, hence the pirate’s current influence.

[Spoilers] To top it all off, FC3‘s ending has two outcomes depending on player choice. The player must ultimately decide for Jason to save his friends and return to his life before the island, and in so doing turn away from the Rakyat and his path with them, or to sacrifice his friends, killing his girlfriend, having sex with Citra, the Rakyat leader, and ultimately dying himself at the hands of Citra.

Both endings show that Jason can never be Rakyat and Jason—he rejects the Rakyat and renews his loyalty to his friends or he rejects his friends and dies, still unable to live with the Rakyat and be one of them. The narrative reinforces the distinct separation between what it means to be a local and an outsider, yet Jason is still the “hero” the Rakyat need.

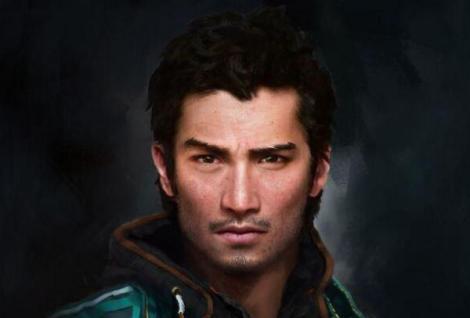

Ajay may have been born in Kyrat, but he is still an outsider and, as such, represents the player as outsider being introduced to the narrative’s conflict. Again, our Westernized protagonist has to determine the fate of a people, solve a problem, and fight. Is the narrative that much different from FC3? Yes and no. Players have to pick sides between the Golden Path’s two leaders, Sabal (a traditionalist) and Amita (a progressive). Players are led to believe their choices will deeply impact the game’s outcome but, as with most games that make such promises, the choices and consequences are limited and artificial at points.

In this game, the local people seem a bit more organic and far less helpless. The Kyrati are a spirited people willing to fight. They are layered and divided on key issues. Tradition clashes with progress. They were colonized by the British years before and are now dealing with the drug trade, weapons, and a struggle to be relevant to the rest of the world. Kyrati culture is embraced and displayed much more prominently than the Rakyat of FC3, especially in the Shangri-La segments. More respect seems to be given to the people’s cultural identity, history, and heritage than in games before, and the protagonist fits into that culture.

The game does make some strides forward. Be it a small point, Ajay is Kyrati and perhaps has some responsibility or call to assist his people, the game is more diplomatic in the approaches you can take to help the Kyrati by giving the player options some weight, and the Kyrati seem more fully realized. Surprisingly, the simple feature of a car radio adds a lot to create and present Kyrati culture. Between the Indian music and the messages from DJ Rabi Ray Rana, I got the sense that the people Ajay was helping were actually dynamic. That they could be real.

Depending on the player’s choices to kill Pagan Min or not and to side with Sabal or Amita, Kyrat is freed to a certain extent. If the player favored Sabal, the country returns to its traditional ways, Amita’s people are killed, and the player is left with one last choice. If Amita was favored, she builds up the army with child soldiers, embraces the drug trade, and rejects the people’s religious beliefs. These endings are more complicated than the two endings in FC3 and perhaps more realistic. A country can be liberated and a war won, but issues persist and something is always lost.

Primal doesn’t seem to take itself too seriously, which is a good thing. There are ample moments of comic relief involving the character Urki, and the Mesolithic period allows for a certain child-like fascination and exploration. I mean, who doesn’t like mammoths and saber-toothed beasts?

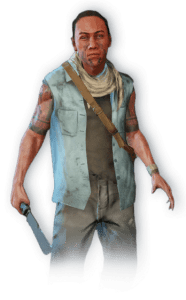

However, the biggest issue I have with Primal is that, while the game has players take on a ‘primitive’ man, one who is an outsider to the groups he is saving, he still looks incredibly like a white, modern man. Consider the following image/avatar of Takkar from the PlayStation store:

As mentioned before, context is key. I have no issue with a video game presenting a narrative of a population in turmoil and in need of a leader. But how the game handles that scenario is where things often get muddied or offensively stereotypical. Does the game question the agency of the protagonist and of the people in need? Is the game designed in a way to prompt questions from the player?

I’m not saying that I didn’t enjoy these games. I enjoyed playing through them, but that doesn’t mean I can’t analyze what I play. Ubisoft has nailed the gun-play and knows how to engage players with the right balance of action, story, and choice. As a result, the Far Cry games are fun. But I would like to see more games, especially open-world ones, that move beyond simply being fun and into the complicated depths of human relationships and power structures.

If a game presents questions, great. But if video game developers continue to present shallow representations of communities and cultures in need that is problematic. Graphical fidelity and hardware have advanced. Isn’t it time our narratives did as well?

One thought on “Unmasking the ‘Savior’: Narratives and Heroes in Far Cry”